Introduction

The phrase “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics," Mark Twain attributed to being said by Benjamin Disraeli, a 19th century Prime Minister of Great Britain. While it gives the impression that statistics are themselves lies, that is not true. It is that numbers, not presented in proper context, can be easily manipulated to give a false impression. A common example are polling results. The results are presented in such a way that a whole population is associated with a portion from a small sample. Typically, pollsters sample any where from 1000 to 2000 people and use the break down to paint a picture of a much larger group. Like the prevalent beliefs of the approximate 38 million residents of Canada. Are we that uniform in thought that querying only 1000 people the pollsters can accurately measure the thoughts and ideals of the population regardless of regional differences? In reality, no. That is why even though they are used to encourage our herd instinct that election results often do not reflect what the pollsters predicted.

But done properly valuable information can be gleaned. To do that every attempt must be made to eliminate any bias, or at least minimise that bias as much as possible. All because facts matter and numbers, if presented properly, do not lie, especially when supported by real data and not just slogans.

Past and Current Issues - audio file

Feature Article

The Facts on Factfulness

I have finished reading the book Factfulness, by Hans Rosling, thoughts on which I would like to share. It was the subtitle that originally caught my interest: Ten Reasons We’re Wrong About the World- And Why Things Are Better Than You Think. In brief it is all about using data to shape our thoughts and ideas. Overall, Rosling does a good job, primarily giving real world examples by using anecdotes to illustrate how reality as supported by data is typically counter to our general beliefs. For example, he begins by posing 13 questions with the third being the question, “In the last 20 years, the proportion of the world population living in extreme poverty has …” with the multiple-choice answers being A: almost doubled, B: remained more or less the same, and C: almost halved. The answer? C, almost halved. Now that is a positive result, and the point of what Rosling is trying to do.

Chapter by chapter he lays out what the problems are that he believes get people to draw the wrong conclusions. Conclusions not supported by the data. In preparing the reader he made these key observations that I, as a data scientist, must agree with: “we need to learn to control our drama intake. Uncontrolled, our appetite for the dramatic goes too far, prevents us from seeing the world as it is, and leads us terribly astray” and “the world is not as dramatic as it seems.” Think of the issues we are being inundated with and the adjectives used to support them. Drama can be considered an understatement based on the doom and gloom that is at their core.

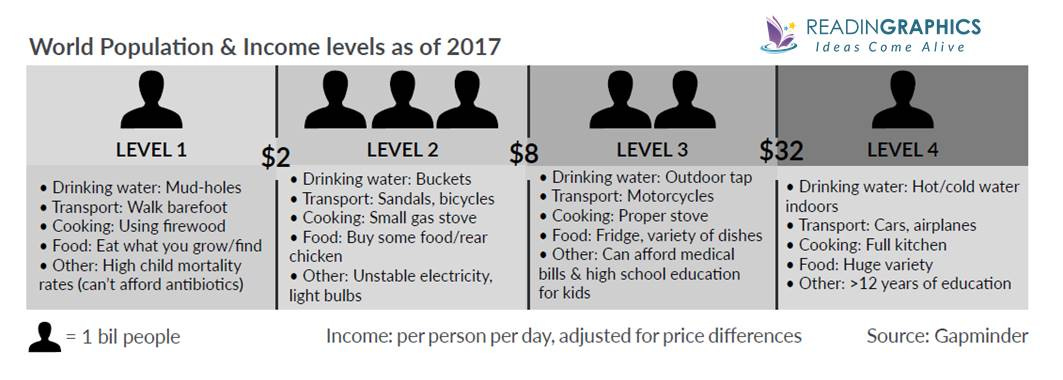

One aspect I really liked was Rosling’s description of why we need to be careful of “The Gap Instinct,” the tendency to separate groups into us and them, which “paints a picture of two separate groups, with a gap in between. The reality is often not polarized at all. Usually the majority is right there in the middle, where the gap is supposed to be.” His recommendation? Look for the majority, beware of comparing averages, and beware of comparing extremes. All, from my own experience very good advice! An example of what he was referring to was dividing the human population into the “Developing World” and the “Developed World.” Or First and Third Worlds. Instead, he proposes dividing the human population into 4 income levels, labeled 1 through 4, with the first being those who live on less than, in adjusted terms allowing for inflation and other factors, 2$ per day, those in Level 2, living on less than $8 per day, those in Level 3 being less than $32 per day and Level 4 being all above $32 per day. This he illustrated as Level 1 being barefoot as they barely make enough to live, Level 2 can afford a bicycle, Level 3 can afford a motorcycle, and Level 4 can afford an automobile. With the prevalence of automobiles, we in Canada obviously fall into Level 4.

From that he made a good point; “Your most important challenge in developing a fact-based worldview is to realize that most of your firsthand experiences are from Level 4; and that your secondhand experiences are filtered through the mass media, which loves nonrepresentative extraordinary events and shuns normality.” It is for this very reason when I had the opportunity to see how others lived, specifically Indonesia, I tried my best to just observe and not make comment based on my experiences in Canada. I do admit I did do exactly that after I spent some time in Australia. But there I was comparing a Level 4 with another Level 4 and while I first thought we shared a lot in common with Australians, in fact culturally we do not. There they have a love-hate relationship with Great Britain and an admiration for the Americans. While the second may be found in Canada, the former is rare.

Chapter 4 is titled “The Fear Instinct” and again, based on my own experiences I cannot disagree. As he states succinctly, “When we are afraid, we do not see clearly.” The last 3 years have been an excellent demonstration of that dictum. All because “Critical thinking is always difficult, but it’s almost impossible when we are scared. There’s no room for facts when our minds are occupied by fear.” To illustrate this point, he reviewed some natural disasters and made the point that deaths have decreased to less than half compared to about one hundred years ago. This conclusion is well supported with data.

With Chapter 5, “The Size Instinct” I found the first inkling that Rosling does not always follow his own advice. He wanted to promote the idea that one must be careful in citing numbers that have not been normalised because to not do so results in an unrealistic understanding. The example he used is CO2 emissions and that China and India pump out far more that any other country in the world. A person from India wanted to downplay this as he felt India was being unfairly targeted and that in reality CO2 should not be reported in absolute values per country but in terms of per person, which Rosling agreed with. If done that way, then countries like Canada have higher per capita emissions. But is that valid?

No, it is not. I spent a significant part of my career estimating the quantity of metal in a mineral deposit and based on my work mining engineers would evaluate whether, at that point in time, the metal could potentially be mined at a profit. To do that I had to normalise by weighting by volume as samples near one another would result in overestimation. In the case of CO2, the issue is not the per capita but the total; how much is being pumped into the atmosphere, as it is the total quantity that is the supposed issue! Thus, countries should be compared by quantity of CO2 per square kilometre and not by per capita. While on a per capita basis Canada may be a “high” emitter with 8 times more than India and twice as high as China, we contribute little to the total. That is the reality, and why he misinterprets his own size instinct – it is not the per person that matters but the per unit area that matters. This is an example of the saying “lies, damn lies, and statistics” in that while the numbers matter, how they are manipulated can introduce an unintended, or intended, bias.

I admit it is an entertaining read with very interesting anecdotes used to emphasise the points he wanted to make. One of these anecdotes about halfway through the book, Chapter 6 of 11, especially caught my interest. The topic of this chapter is “The Generalization Instinct” where he cautions about generalising between different groups. The specific anecdote is that back in 1974 he believed that babies should be placed, when sleeping, on their stomach and not on their back based on the prevalent belief at that time that babies, like adults who are at risk should be left in “the recovery position” and thus on their stomachs. The thought being that would prevent babies from succumbing to sudden infant death syndrome, SIDS, due to the risk of suffocation. Research has since shown that this was not a warranted action; a sleeping baby is not the same as an unconscious adult. He admits he was wrong in purposely turning babies onto their stomachs based on bad data, and specifically it is not appropriate to generalise. As he himself says, “We must all try hard to discover the hidden sweeping generalizations in our logic.”

It is in the later chapters that the wheels really start to fall off with blatant inconsistencies. For example, in Chapter 10, “The Urgency Instinct.” Near the beginning of this chapter, he states “When we are afraid and under time pressure and thinking of worst-case scenarios, we tend to make really stupid decisions. Our ability to think analytically can be overwhelmed by an urge to make quick decisions and take immediate action.” Soon after he follows with his own “stupid decision” in that he says the following: “To be absolutely clear, I am deeply concerned about climate change because I am convinced it is real.” And what data does he use to substantiate this decision? “Thanks to great satellite images, we can track the North Pole ice cap on a daily basis. This removes any doubt that it is shrinking from year to year at a worrying speed. So we have good indications of the symptoms of global warming. But when I looked for the data to track the cause of the problem—mainly CO2 emissions—I found surprisingly little.”

First, there is no “North Pole Ice Cap!” That pole is close to the centre of the Arctic Ocean and covered by sea ice. Ice that often is partially melted during the short mid-summer thanks to 24 hours of sunshine. The only time of year that ocean is not fully covered by ice and when light conditions are such you can have satellite imagery. That imagery proves nothing yet is used as fodder for those who promote fear, an emotion Rosling says one should not allow to control your thinking. Yet he does. And he follows this with a statement saying the CO2 data does not support the conclusion he made!

Overall, it is a good read, but I found the author too arrogant at times compounded by his falling into the same traps he warns the reader not to do. Like over generalising, introducing size bias, plus letting urgency and fear cloud his thinking. Yet, I was disappointed. Not that he believes in human-caused climate change, something I do not. But because for this topic he threw out the reason for the book, letting the real data guide you. After decades of looking diligently I have been unable to find any data in support of human caused climate change or that CO2 is an issue. How? By always relying on facts, something Rosling is unable to do himself; while he talks the talk, he is unable to walk the walk.

By: Alan Aubut